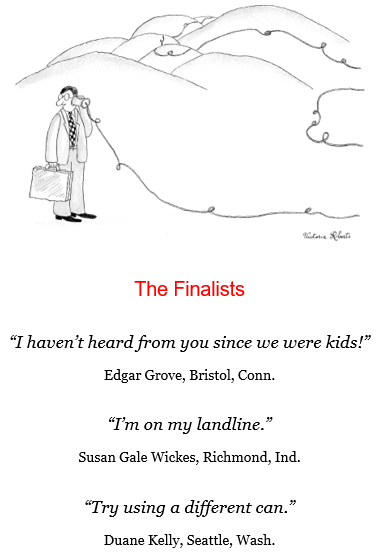

Last month The New Yorker magazine sent a decree throughout the land that my cartoon caption for its August 29 contest was one of three finalists. I guess the sheer brilliance of “Try using a different can” could not be denied. Hoorah, hoorah!

Last month The New Yorker magazine sent a decree throughout the land that my cartoon caption for its August 29 contest was one of three finalists. I guess the sheer brilliance of “Try using a different can” could not be denied. Hoorah, hoorah!

I have long used the weekly magazine’s caption contest as a comic writing exercise, low-impact training for my scriptwriting. A play can always use one more laugh. My caption achieving finalist status got me thinking about luck and artistic success – a marriage I frequently interrogate. When The New Yorker’s cartoon department informed me I was a finalist, it so happened that I was in Edinburgh, far from my Seattle home. I was on the other side of the world to support the production of my play Visiting Cezanne at the Fringe Festival. In that play a despairing Paul Cezanne – in his pre-fame life – tells another artist, also in despair: “Hanging on the walls of the Louvre are a few grains of sand kicked up from a desert bigger than the Sahara.” As a young artist Cezanne had spent countless hours at the Louvre, studying and copying and – or so the author imagines – dreaming.

Each week The New Yorker receives more than 5,000 captions for its contest. Was my “Try using a different can” better than 4,997 other entries? I rather doubt it. I believe that most of us – artists and not – underestimate the role of luck in our lives. There is an adaptive benefit to this. If success is just a random coin toss, why try? The more control we think we have over our fate, the more agency we are likely to assert. And when we do taste success we are inclined to attribute it to our own amazing abilities, whereas failure, why that is caused by external factors beyond our control. Otherwise known as luck. Research psychologists call this “attribution bias.” E.B. White captured this trait with the quip: “Luck is not something you can mention in the presence of the self-made man.” Whereas in sports and business batting averages and profit/loss make the job easier, the bias is harder to sustain in the arts. How to judge which grains of sand kicked up from the Sahara should hang on the walls of the Louvre? Many artists land on those walls by dint of hard work but multiples more have worked their tails off without fame or fortune ever showing up. Effort may be necessary for success, but it is not sufficient by itself.

How long have I been doing this New Yorker caption thing? I had to go back and check. The August 29 drawing by Victoria Roberts was contest no. 814. The first caption I submitted was way back in December, 2008 for contest no. 172. I don’t believe I’ve ever missed a contest, which would mean that I have proffered captions for 642 cartoons. My practice is to spend a half-hour each week inventing ten to twenty captions, then send in the one I judge best. This process observes screenwriter guru Robert McKee’s rule of thumb that out of every ten story concepts or plot points you invent, only one has merit. And that’s on a good day. The other nine stinkers are the price you pay to earn the one that may be half-decent. My captions have competed with 3,210,000 others (642 contests X 5,000 submissions). Out of three million-plus captions, I’ve had one selected. I try not to think about how many new plays get written each year, and how few full production opportunities there are for them.

My caption was just one of three finalists. A fellow from Connecticut ended up the winner. His entry? “I haven’t heard from you since we were kids.” Not bad.

Don’t miss a thing. Receive Duane’s infrequent blog posts by signing up on the Home or Contact pages of this website.